Often, students in biology and paleontology wonder why it is that we “force” them to take physics. I ought to know — I was one of those students! It wasn’t until later in graduate school that I began to appreciate the application of physics to matters of dinosaur movement. I believe part of this reticence among many future biologists and paleontologists to embrace and understand physics is that they feel (as I once did) that it was mostly the arena of engineers and cosmologists.

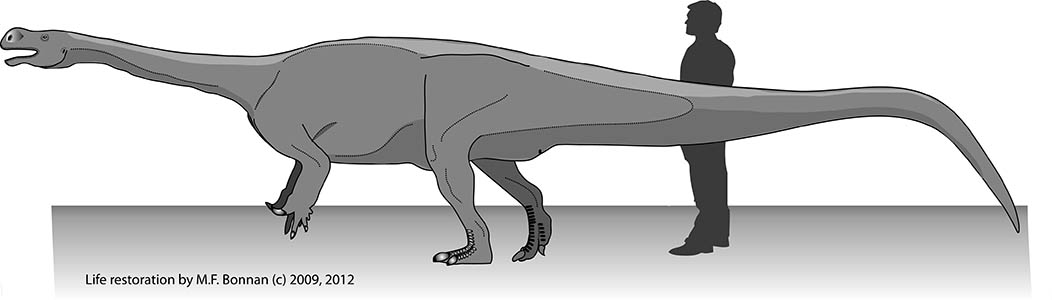

Yet, the questions we are often so interested in about living organisms and those in the fossil record relate to physics. How did they move? Were they moving in water? How could their heart pump blood to their head? How did a giant sauropod move, let alone stand, without breaking its bones? So, if you are interested in dinosaurs and other magnificent animals of the past in the context of how they went about their daily lives, then you are interested in physics.

When I first began teaching vertebrate paleontology back in 2003, my goal then as now was to communicate to biology and paleontology students how modern vertebrate skeletons and body form are related to their function. Too often, in my opinion, we tend to emphasize taxonomy and relationships over how, as scientists, we reconstruct paleobiology. To be clear, taxonomy and the study of evolutionary relationships (systematics) are hugely important — they provide the context in which we test evolutionary hypotheses. However, I wanted to strike a balance in my courses of teaching how the vertebrates were related in combination with how they lived their lives and responded to the physical world.

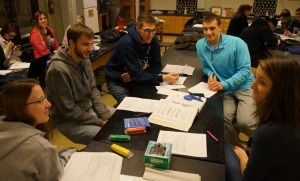

Today in my vertebrate paleontology course at Richard Stockton College, I hope a new group of students has begun to appreciate this intersection among biology, paleontology, and physics. In the lab, students used a small wind tunnel and “smoke” from a fog machine to test how three different fossil fishes may have moved through the water. I have found it is one thing to talk about Bernoulli’s Principle or discuss friction and pressure drag. It is a whole other kettle of fish (pun intended) to see for one’s self how body shape actually changes the fluid around it.

Each group of students was assigned a fossil fish to research and model out of clay in lab. Then, after hypothesizing how they thought their particular fish would behave relative to the water current (or in this case, the air current with “smoke”), they put their models in the wind tunnel, turned on the smoke, and put their hypotheses to the test. They will later present their findings to the class. My hope in all of this is that these students appreciate that our hypotheses about past life rely heavily on our models of the present flesh, bone, and physical laws.

Student group modeling and studying the effect of body shape on fluid movement in the early chondrichthyan, _Cladoselache_. Our wind tunnel can be seen in the background, upper left.

The _Hemicyclaspis_ model in our wind tunnel, sitting on a box of clay to prop it into the (faintly visible) stream of “smoke.”

I want to dedicate this short post to the following people at Richard Stockton College. First, having a wind tunnel and smoke machine would not have happened at all were it not for the help of our shop staff in the Natural Sciences — Bill Harron, Mike Farrell, and Mike Santoro. They worked on this small scale wind tunnel with my input, and helped give our students a wonderful lab experience.

Second, Christine Shairer was invaluable for her help with getting me the materials my students and I needed to do this small-scale experiment.

Finally, third, Dr. Jason Shulman in physics who is a colleague, research collaborator, and one of the few physicists willing to put up with a paleontologist who is constantly asking what I can only assume are ignorant and humorously simple questions. If only I had had such an enthusiastic professor when I was questioning why I had to learn physics all those years ago!