In paleontology, we often infer the habits and behaviors of fossil vertebrates by reference to their skeletal shape. However, it is often difficult to appreciate what those shapes are telling us: how well does shape correlate with motion?

We are members of the eutheiran branch of the mammal family tree. Among many questions concerning mammal evolution, one is how did the earliest eutherian (so-called “placental”) mammals use their forelimbs? This question has important implications for how our earliest relatives got around. The earilest known members of our group are small and are often hypothesized to be scansorial (Luo et al., 2003, 2011), meaning that they are at home on the ground as well as clambering up trees.These inferences are drawn in large part from the form of the fossilized forelimb bones and their presumed functions.

If you’ve been following this blog, you know that I have been immersed in learning XROMM (X-ray Reconstruction of Moving Morphology), a technique that combines video fluoroscopy (X-ray movies) with registration of three-dimensional bone models to yield 3-D moving X-rays.

I am happy to report that my colleagues, two Stockton undergraduates (Radha Varadharajan and Corey Gilbert), and I have published an Open Access article in PLoS One that, for the very first time, reconstructs the three-dimensional movements of the long bones (humerus, radius, ulna) in the forelimb of rats. Why rats? Rats have a forelimb anatomy that is very similar in many ways to those of the earliest eutherian mammals, and as a plus, rats are scansorial. Rats are also relatively easy mammals to work with in the lab (although some days they out-clever the humans) and can be trained. As a fun side note, we named two of the rats Pink and Floyd.

Our setup was straightforward — at the C-arms XROMM lab at Brown University, the rats walked along a plank of wood to a darkened hide box. While traversing the plank, they made their X-ray cameos in two fluoroscopes connected to hi-speed cameras filming at 250 frames per second (your iPhone camera films at 30 frames per second in normal mode). When we were finished collecting our data, the rats were CT-scanned so that we could have exact three-dimensional models of their limb bones. The most painstaking part was the several months it took to digitize each of our good trials. That is, using animation software, we had to match the bone models up to their X-ray shadows in the two calibrated fluoroscope movies. Once this was accomplished, our task turned to watching how the bones moved in three-dimensional space as well as analyzing the joint angle data that was generated.

Our basic setup for the XROMM study — rats were trained to walk across a plank towards a dark hide box, leading them between the two videofluoroscopes.

What we found both confirms previous work on small mammal locomotion, but added some interesting new insights as well. As a general rule, small mammals have a crouched posture where the elbows and knees are bent. This type of posture may aid small mammals in maneuvering around objects and keeping a lower center of gravity, which would enhance stability, especially on branches and other narrow perches. Not surprisingly and given previous work on rat locomotion, we see that these mammals do indeed walk on crouched limbs — the elbow angle, for example, never exceeded 123 degrees in full extension. By way of comparison, your elbow can be extended to 180 degrees.

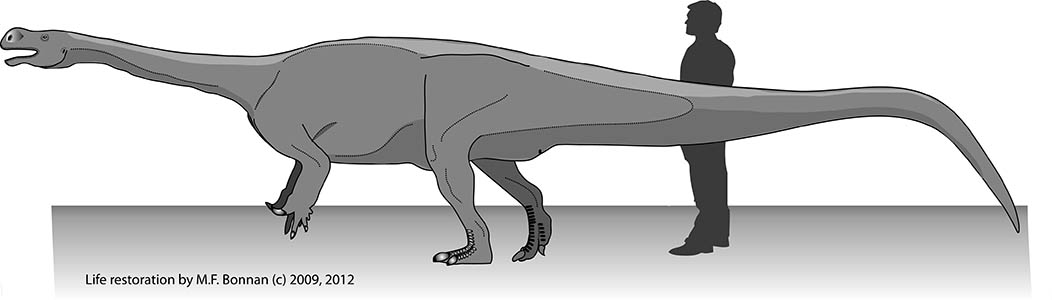

A figure from my book, The Bare Bones. Note how the rat has a more crouched posture whereas the cat is more upright.

However, we often get the impression that mammal locomotion is similar at different scales. From cats and dogs on up, it appears that the forelimbs and hindlimbs function very much as glorified pendulums. In essence, eutherian mammal locomotion is understood as mostly two-dimensional. Although rats are small and have a crouched posture, their limb bones would be presumed to follow the pendulum model.

But what the bones were doing in three-dimensions was fascinating. Both the humerus (upper arm bone) and radius (the forearm bone that aligns with your thumb) showed they were capable of long-axis rotation. Long-axis rotation is similar to the way a lathe or axle spins. Our rats’ bones certainly weren’t spinning on their long-axis, but they did show a non-trivial range of movement. A step cycle consists of a stance phase (when the hand is on the ground and forelimb is supporting the body) and a swing phase (when the hand is off the ground and the forelimb is swinging back to support the body for the next step). We found that during stance, the humerus both moves toward the midline (adducts) and rotates on its long axis towards the body. These combined movements appear to ensure that the elbow points backwards so that the forearm maintains an upright posture. During swing, the humerus moves away from the body midline (abducts) and rotates on its long axis away from the body. These combined movements seem to allow the forelimb to clear the rat’s body as the limb is brought forward to start a new step.

Lateral (side), ventral (belly), and radioulnar joint (at the elbow) views of the humerus (sea green), radius (black), and ulna (red) in a typical step cycle in Rattus norvegicus. Long-axis rotation (LAR) of the radius about the ulna (radius pronation) is shown in cranial view (the rat is walking toward you) from the perspective of the ulna (the ulna appears to be stationary in the radioulnar joint view relative to the humerus and radius). Note radius (black) LAR relative to the ulna (red). Percentages = portion of the step cycle. Black bar in ventral view = body midline based on sternum.

MOVIE 2 – One of our rats, “Floyd,” demonstrating a typical step cycle.

What was particularly exciting to me was that we saw, for the first time in rats, the radius pivot about the ulna! In humans, we take these movements for granted: our radius pivots around our ulna with ease, directing our palms either downward (pronated) when its shaft cross over the ulna, or upward (supinated) when its shaft rotates into parallel with the ulna. Up until now, it has been unclear if the radius could move in this way to flip the hand palm-side down in rats, or whether their hand posture was maintained via positioning of the limb in general. We now know that, indeed, the radius does move and does appear to be correlated with hand placement in rats. These movements are much more subtle than in you and I (in our rats a range of 10-30 degrees of rotation), but they appear to be correlated with pronation of the hand.

MOVIE 3 – One of our rats, “Floyd,” showing how the radius pivots on the ulna during a step cycle.

Our research has two messages. The first message is that given the similarities in the forelimb skeletons of the earliest known eutherian mammals (Juramaia and Eomaia) to those of rats, it is likely that a similar range of movements were possible in these distant relatives on our family tree. Paleontologists studying these fossils, such as Zhe-Xi Luo and colleagues (Luo et al., 2003, 2011), have already suggested these early eutherian mammals were scansorial, and our data bolster their hypothesis. These sorts of insights are helpful in constraining when particular locomotor behaviors and movements became possible and how that might have effected mammalian evolution.

The second message is that small mammal locomotion is probably not as similar to those of larger mammals as we often think, a sentiment echoed by the late Farish Jenkins (e.g., Jenkins, 1971) and by Martin Fischer and his colleagues (Fischer et al. 2002; Fisher and Blickman, 2006). Moreover, our rat data show that, at least for the forelimb, long-axis rotation plays a role in normal overground movement.

We hope our study provides another perspective on small mammal locomotion and encourages new and fruitful research in our furry friends past and present.

————————

I am grateful to my colleagues and former students for their help and work on this project. I want especially to thank Elizabeth Brainerd (Brown University). She has been a source of encouragement and a patient teacher to an old dinosaur learning new tricks, and her help with learning XROMM and on designing the experiment which led to this paper (my first foray into animal kinematics) was invaluable.

The authors of the paper (* indicates a Stockton University undergraduate)

Matthew F. Bonnan (Stockton University, Biology)

Jason Shulman (Stockton University, Physics)

*Radha Varadharajan (Stockton University, Biology)

*Corey Gilbert (Stockton University, Physics)

Mary Wilkes (Stockton University, Biology)

Angela Horner (California State University, San Berardino)

Elizabeth Brainerd (Brown University)

———————–

References

Fischer, M. S., and R. Blickhan. 2006. The tri-segmented limbs of therian mammals: kinematics, dynamics, and self-stabilization—a review. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Comparative Experimental Biology 305A:935–952.

Fischer, M. S., N. Schilling, M. Schmidt, D. Haarhaus, and H. Witte. 2002. Basic limb kinematics of small therian mammals. The Journal of Experimental Biology 205:1315–38.

Jenkins, F. A. 1971. Limb posture and locomotion in the Virginia opossum (Didelphis marsupalis) and in other non-cursorial mammals. Journal of Zoology, London 165:303–315.

Luo, Z.-X., Q. Ji, J. R. Wible, and C.-X. Yuan. 2003. An Early Cretaceous Tribosphenic Mammal and Metatherian Evolution. Science 302:1934–1940.

Luo, Z.-X., C.-X. Yuan, Q.-J. Meng, and Q. Ji. 2011. A Jurassic eutherian mammal and divergence of marsupials and placentals. Nature 476:442–445.