You can read the paper for free by clicking here.

As I recently learned from a fall in which I broke one of my ribs, gravity is an irresistible force.

My poor broken rib.

Gravity’s relentless pull has shaped the evolution of the skeleton in land vertebrates who have had to stand tall or be crushed. Trees have it easy in that they only have to stand and sway (Vogel, 2003) – our skeletons have to resist gravity while on the move (McGowan, 1999; Carter and Beaupré, 2001). If force equals mass times acceleration, then every time you walk, jog, or climb a flight of stairs, you are pummeling your limb skeleton with forces greater than your body weight! But your bones are alive and they adapt to this daily abuse by changing their shapes to best resist those forces. Therefore, paleontologists, like my colleagues and I, are obsessed with bone shape because it is a proxy record of how the limb skeleton adapted to support and move a fossil animal like a dinosaur. Until we recreate living dinosaurs ala Jurassic Park, limb shape is the next best thing to putting a dinosaur or mastodon on a treadmill.

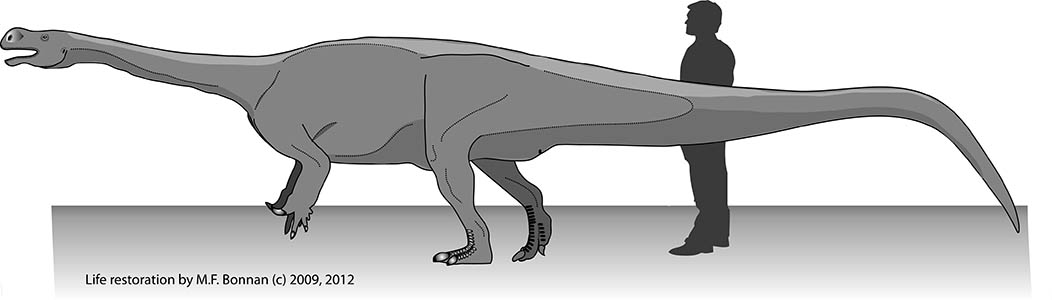

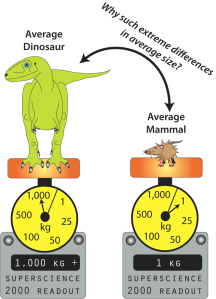

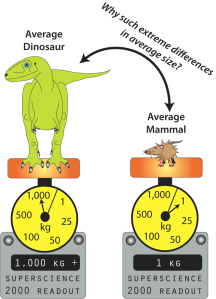

Many dinosaurs were successful in becoming land giants, whereas a comparative handful of land mammals have ever crossed the 1,000 kg mark (Farlow et al., 1995, 2010; Prothero and Schoch, 2002; Prothero, 2013).

The average dinosaur (excluding birds) weighed in at over 1 ton, whereas the average land mammal barely tips the scales at 1 kilogram. (c) 2013 M.F. Bonnan.

Therefore, you might predict to see stark differences in limb skeleton shape between dinosaurs and land mammals … and yet you don’t! In fact, getting big on land as a dinosaur or mammal usually results in stout columnar limb bones which resist weight combined with a decrease in activities like running or jumping (Christiansen, 1997, 2007; Carrano, 2001; Biewener, 2005; Bonnan, 2007). In essence, you get an interesting but ultimately boring pattern that shows us there are only so many solutions to fighting gravity.

In a recently published open-access, peer-reviewed article in PLOS ONE, my colleagues and I have shown that there is one area of a limb bone that does change in different ways with increasing size between land mammals and dinosaurs: the joint-bearing region.

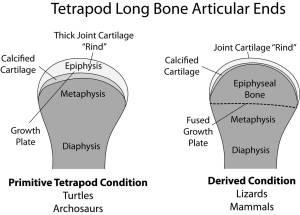

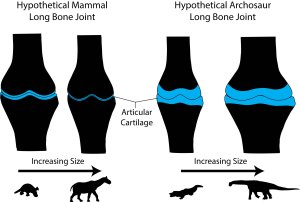

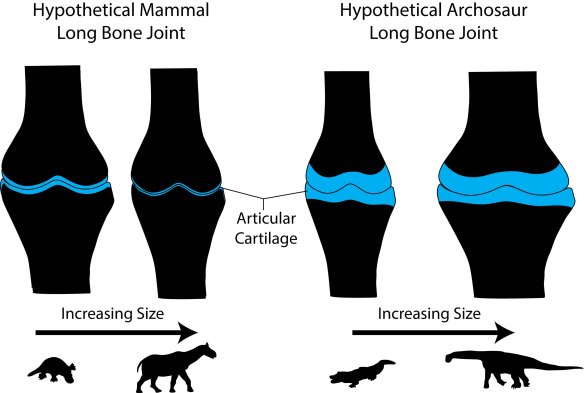

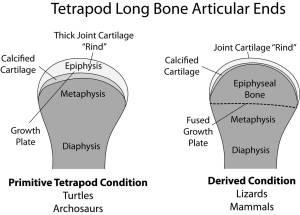

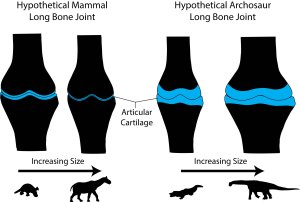

Dinosaurs share the primitive tetrapod condition of retaining thick cartilaginous joints. Diagram by Bonnan after Carter & Beaupre (2001) and Holliday et al. (2010).

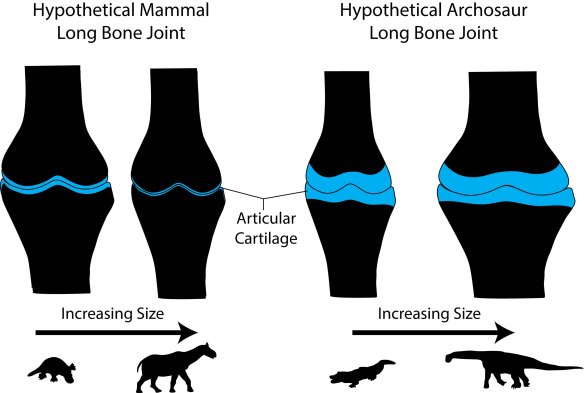

Called the sub-articular surface, this zone supports the slippery and pliable articular cartilage that makes movement possible at joints by decreasing friction and absorbing stress. We focused on this region because: 1) its shape should reflect how the bone beneath the cartilage was reacting to stress; and 2) recent work has shown that articular cartilage thickness in dinosaurs and land mammals differs, being very thick (several centimeters in some cases) in the former and very thin (only a few millimeters) in the latter (Graf et al., 1993; Egger et al., 2008; Bonnan et al., 2010; Holliday et al., 2010; Malda et al., 2013).

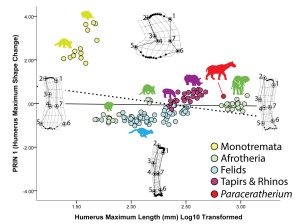

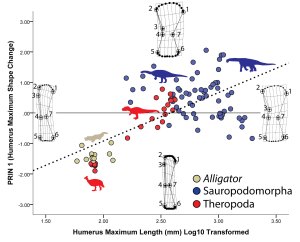

What we found surprised us. As land mammals become giants, their sub-articular regions become narrow with well-defined surface features. In contrast, becoming a giant sauropod involves an increase in the sub-articular region combined with a subdued, gently convex profile.

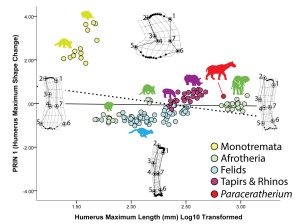

Figure 3 from our PLOS ONE paper — On the X-axis, the sub-articular bone region narrows significantly with increasing size, and the shapes of these regions become more convex and/or distinct.

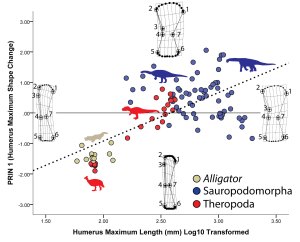

Figure 5 of our PLOS ONE paper — . Along the X-axis, the sub-articular region of the humerus expands tremendously whereas its overall shape remains gently convex.

Why this difference? Our results suggest two interrelated relationships. First, sub-articular bone profile and cartilage thickness go hand-in-hand. In living animals, those with thick articular cartilage (alligators and guinea fowl birds in our sample) have expanded sub-articular regions with gentle convexity, whereas those with thin articular cartilage (the living mammals in our sample) retain narrow and increasingly well-defined sub-articular regions. Hence, seeing the narrow and well-developed sub-articular regions in fossil elephants and Paraceratherium show convincingly that they had very thin articular cartilage. In contrast, the expanded and gently convex ends of the limb bones in sauropods appear to be well-correlated with thick articular cartilage.

Second, and more intriguing, these differences suggest different adaptations to becoming a giant constrained by cartilage thickness. In mammals, it has been well-documented that the best way to disperse stress through thin cartilage is to increase the surface contact area (Simon et al., 1973; Egger et al., 2008). In other words, mammals spread the load by narrowing their joints and increasing surface complexity, allowing the bones to articulate closely. As we say in the paper, becoming a giant mammal means developing highly congruent joints. In contrast, becoming a giant sauropod dinosaur involves retaining thick articular cartilage that presumably deforms under pressure. This would go a long way to explaining the expanded sub-articular surfaces we see in sauropods: deforming a thick block of cartilage safely likely requires enough space over which to spread the load.

What does this all have to do with the frequency of gigantism? We speculate that articular cartilage thickness may have a limiting effect on size. If in mammals the best way to spread stress through a joint is by thinning the cartilage and increasing congruence, you are going to get to a point where the joints are as congruent as possible and the cartilage cannot get any thinner. In contrast, retaining thick articular cartilage at large size might have been one factor that contributed to the frequent evolution of so many dinosaur giants. Therefore, our data suggest that the rarity of large land mammals may be due, in part, to their highly congruent limb joints with thin articular cartilage, whereas the success of sauropod dinosaurs as giants may be tied, in part, to their retention of thick articular cartilage.

Figure 7 from our PLOS ONE paper — This figure conveys the essence of our conclusions: as mammals become giants, their joints become ever more congruent with thinning articular cartilage. For dinosaurs, the cartilage remains thick and the joint region expands.

As we say in the article, we in no way intend this to be the last word on dinosaur gigantism or imply that this was the only explanation for their success as land giants. In fact, we hope our work, which was limited to 2-D profiles of the sub-articular surfaces, will be expanded upon using newer, 3-D technology by future researchers (see for example recent work by Tsai and Holliday [2012]). So the next time you take a walk, think about and appreciate how a narrow slice of cartilage helps ensure your bones glide past one another and don’t smack together. I only wish thick, pliable cartilage was in my poor rib, which deformed and snapped under stresses far, far less than those which pummeled the limbs of giant mammals and dinosaurs.

My poor broken rib revisited.

You can read the paper, for free, here.

My Co-authors

This study would not have been published without the help and perseverance of my co-authors.

Ray Wilhite is a kindred sauropod spirit, and an associate professor of veterinary anatomy at Auburn College who knows far more about alligator anatomy than I can ever hope to amass. His assistance in helping me twice procure, dissect, and prepare alligators from the Louisiana Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge was invaluable. He also introduced me to Ruth Elsey, the goddess of alligators, whom ended up as an author on one of our previous forays into the relationship between cartilage thickness and shape (Bonnan et al., 2010).

Ray Wilhite is a kindred sauropod spirit, and an associate professor of veterinary anatomy at Auburn College who knows far more about alligator anatomy than I can ever hope to amass. His assistance in helping me twice procure, dissect, and prepare alligators from the Louisiana Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge was invaluable. He also introduced me to Ruth Elsey, the goddess of alligators, whom ended up as an author on one of our previous forays into the relationship between cartilage thickness and shape (Bonnan et al., 2010).

Ray comments on our paper: “For most of the history of vertebrate paleontology scientists and explorers focused on finding new fossils and organizing them into meaningful taxonomic groups. Recently, however, many paleontologists have shifted their focus to trying to understand the biology and functional morphology of extinct species. I believe our study has moved the discussion forward regarding the morphological adaptations of sauropods that allowed the to grow to such gigantic proportions. Our study provides a possible clue about why sauropod humeri and femora have expanded ends and large terrestrial mammals do not. The revelation in recent years that there is most likely a significant portion of the articular surface missing in preserved sauropod limb bones is supported by this study. Slowly but surely we are beginning to not just put flesh on the bones, but put the bones on the bones and see what lay between.”

Simon L. Masters was a former graduate student of mine, and his thesis on the ontogeny of the forelimb in Allosaurus was to  form the basis of the theropod dinosaur set in our paper. Simon, along with Jim Farlow, previously helped with the writing and analysis of using shape-based statistics for determining sex from the alligator femur (Bonnan et al., 2008). Simon has done well for himself and I’m happy to say he is inspiring a new crop of STEM students as a high school teacher at the all-girls Beaumont School in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.

form the basis of the theropod dinosaur set in our paper. Simon, along with Jim Farlow, previously helped with the writing and analysis of using shape-based statistics for determining sex from the alligator femur (Bonnan et al., 2008). Simon has done well for himself and I’m happy to say he is inspiring a new crop of STEM students as a high school teacher at the all-girls Beaumont School in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.

Adam M. Yates has been an invaluable friend and colleague, and his contribution to this paper allowed us to compile a great deal of morphometric data on “prosauropods.” More specifically, when he, Johann Neveling, and I were working up a different paper on what would become our new dinosaur, Arcusaurus (Yates et al., 2011), I began running morphometric analyses of the distal ends of dinosaur and archosaur humeri because we had only the distal end of that animal’s humerus. That figure never made the final paper but it was my first hint that something interesting was going on in dinosaurs: as I plotted “prosauropod” and sauropod humeri, I could see that there was this trend towards expansion and slight convexity. I wanted to note that in our Arcusaurus paper, but Adam encouraged me to save the data for a later time … and that time is now.

Adam M. Yates has been an invaluable friend and colleague, and his contribution to this paper allowed us to compile a great deal of morphometric data on “prosauropods.” More specifically, when he, Johann Neveling, and I were working up a different paper on what would become our new dinosaur, Arcusaurus (Yates et al., 2011), I began running morphometric analyses of the distal ends of dinosaur and archosaur humeri because we had only the distal end of that animal’s humerus. That figure never made the final paper but it was my first hint that something interesting was going on in dinosaurs: as I plotted “prosauropod” and sauropod humeri, I could see that there was this trend towards expansion and slight convexity. I wanted to note that in our Arcusaurus paper, but Adam encouraged me to save the data for a later time … and that time is now.

Christine Gardner was one of my many successful undergraduate honors students. While working with me, she measured nearly all of the Afrotherian mammals in our paper for her undergraduate thesis on long bone scaling in these mammals. Her hard work at collecting and analyzing her dataset not only gave her honors in finishing her undergraduate work, but contributed in a substantial way to our paper. She has also journeyed with me out to the field a number of times, and has successfully landed herself in the graduate program at the South Dakota School of Mines.

Christine Gardner was one of my many successful undergraduate honors students. While working with me, she measured nearly all of the Afrotherian mammals in our paper for her undergraduate thesis on long bone scaling in these mammals. Her hard work at collecting and analyzing her dataset not only gave her honors in finishing her undergraduate work, but contributed in a substantial way to our paper. She has also journeyed with me out to the field a number of times, and has successfully landed herself in the graduate program at the South Dakota School of Mines.

Christine had this to say about our study: “It was the summer between my junior and senior years when I officially began my undergraduate thesis project. Obviously a new experience for me, I didn’t entirely know what to expect. Little did I know I’d watch my raw data not only yield my honors thesis, but eventually become part of much bigger research which has ended with my name being published. Not many students get to share this privilege before finishing their Master’s thesis.”

Adam Aguiar is one of my new colleagues at the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey who specializes is understanding the molecular-level details of bone and cartilage biology. After the first draft of the paper, he was invaluable at providing insight into thinking about articular cartilage and its responses to shock and stress. This gave the paper a new lease on life, and I doubt we would have been successful on our next submission had it not been for his encouragement and contribution.

Adam Aguiar is one of my new colleagues at the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey who specializes is understanding the molecular-level details of bone and cartilage biology. After the first draft of the paper, he was invaluable at providing insight into thinking about articular cartilage and its responses to shock and stress. This gave the paper a new lease on life, and I doubt we would have been successful on our next submission had it not been for his encouragement and contribution.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many institutions and individuals that provided us with access to specimens for this study. I cannot possibly list all of them here: much of the archosaur data was collected for previous studies (Bonnan, 2004, 2007; Bonnan et al., 2008, 2010) and the heartfelt thanks and appreciation expressed in those references continues more strongly than ever here. For the present study, we wish to thank the following institutions and staff: AMNH: N. B. Simmons and staff (Mammalogy), J. Meng, J. Galkin, and staff (Fossil Mammals); FMNH: W. Stanley and staff (Mammalogy), K. D. Angielczyk, W. Simpson, and staff (Fossil Mammals); UNMH: R. Irmis, M. Getty, and staff; CLQ: M. Leschin; SAM: A. Chinsamy-Turan and staff; BPI: B. Rubidge and staff. We thank Kimberley Schuenman at WIU for collecting data on felids used in this study. Feedback from Gregory S. Paul, Henry Tsai, and Stephen Gatesy at the 2012 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting further improved our manuscript. Discussions with Jason Shulman at the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey on static physics were helpful. Donald Henderson and an anonymous reviewer provided useful comments, critiques, and suggestions on a first draft of this manuscript. We are also indebted to PLOS ONE editor Peter Dodson for shepherding our manuscript through the PLoS system, and his feedback, comments, and suggestions.

Last but not least – a great big thank you to my new employer, the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, for helping with publication costs! Thank you Stockton and the Grants Office, particularly Beth Olsen!

An Important Aside on Methods and Why We Did What We Did

- We chose to focus on evolutionary lines of mammals and dinosaurs that gave rise to the very largest land species. For mammals, we focused on the placental (eutherian) lines called Afrotheria and Laurasiatheria because elephants and Paraceratherium, the giant rhino relative, descended from these. For dinosaurs, we focused on the Saurischians because the giant, long-necked “brontosaurs” called sauropods were members. We also selected smaller-bodied relatives of these giants in their family trees to examine how similar or different the sub-articular zones of these giants were to their smaller relatives. To analyze shape, we used a computer program called Thin-Plate Splines that tracks and compares landmark coordinates on bones.

- Because bony landmarks and sub-articular surfaces were not always anatomically homologous between archosaurs and mammals, we avoided issues of mixing non-homologous areas in our data by running the analyses on these two groups separately.

- Why did we use a two-dimensional analysis instead of a three-dimensional analysis? Undoubtedly, three-dimensional shape analysis would have further enhanced our interpretation of sub-articular shape patterns. However, a number of challenges prevented such an approach:

- First and most significantly, the data collected in this study span a period of over 10 years during which time cost-effective and portable three-dimensional scanning technologies for acquiring large bone geometries have only recently started to become available. Had we access to these technologies ten years prior, we would have utilized them, as we plan to utilize such approaches in future studies.

- Second, our main goal in this study was to quantify whether or not there were significant differences in the scaling patterns of surface morphology between eutherian mammal and saurischian dinosaur long bones, and whether such differences were correlated with known differences in articular cartilage properties. We emphasize that our goal was not to realistically recreate joint surfaces or establish precise measures of joint articulation, nor do we propose how the three-dimensional shape of the subchondral bone is used to reconstruct joint geometry. Our selection of the humerus and femur furthers our goal: these are long bones in which a significant portion of the subarticular surfaces can be reliably captured and interpreted in two dimensions.

- Finally, third, two-dimensional data is valuable, comparable to previous studies, and provides a good first-level approximation of scaling patterns. Just as linear morphometrics informed and directed the study of two-dimensional geometric morphometrics (GM) of long bones, so, too, can two-dimensional GM illuminate where future three-dimensional GM studies can make the best impact. Our study is certainly not the last word on long-bone scaling and subarticular patterns in non-avian dinosaurs. Rather, we hope it inspires and provides the basis for research incorporating three-dimensional technologies in years to come.

References

Biewener, A. A. 2005. Biomechanical consequences of scaling. The Journal of Experimental Biology 208:1665–76.

Bonnan, M. F. 2004. Morphometric analysis of humerus and femur shape in Morrison sauropods: implications for functional morphology and paleobiology. Paleobiology 30:444–470.

Bonnan, M. F. 2007. Linear and geometric morphometric analysis of long bone scaling patterns in Jurassic neosauropod dinosaurs: their functional and paleobiological implications. Anatomical Record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007) 290:1089–111.

Bonnan, M. F., J. O. Farlow, and S. L. Masters. 2008. Using linear and geometric morphometrics to detect intraspecific variability and sexual dimorphism in femoral shape in Alligator mississippiensis and its implications for sexing fossil archosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28:422–431.

Bonnan, M. F., J. L. Sandrik, T. Nishiwaki, D. R. Wilhite, R. M. Elsey, and C. Vittore. 2010. Calcified cartilage shape in archosaur long bones reflects overlying joint shape in stress-bearing elements: Implications for nonavian dinosaur locomotion. Anatomical Record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007) 293:2044–55.

Carrano, M. T. 2001. Implications of limb bone scaling, curvature and eccentricity in mammals and non-avian dinosaurs. Journal of Zoology 254:41–55.

Carter, D. R., and G. S. Beaupré. 2001. Skeletal Function and Form : Mechanobiology of Skeletal Development, Aging, and Regeneration. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; New York, pp.

Christiansen, P. 1997. Sauropod locomotion. Gaia 14:45–75.

Christiansen, P. 2007. Long bone geometry in columnar-limbed animals: allometry of the proboscidean appendicular skeleton. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149:423–436.

Egger, G. F., K. Witter, G. Weissengruber, and G. Forstenpointner. 2008. Articular cartilage in the knee joint of the African elephant, Loxodonta africana, Blumenbach 1797. Journal of Morphology 269:118–127.

Farlow, J., P. Dodson, and A. Chinsamy. 1995. Dinosaur biology. Annual Review of Ecology and \ldots 193:44.

Farlow, J., I. D. Coroian, and J. Foster. 2010. Giants on the landscape: modelling the abundance of megaherbivorous dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic, western USA). Historical Biology 22:403–429.

Graf, J., E. Stofft, U. Freese, and F. U. Niethard. 1993. The ultrastructure of articular cartilage of the chicken’s knee joint. Internationl Orthopaedics (SICOT) 17:113–119.

Holliday, C. M., R. C. Ridgely, J. C. Sedlmayr, and L. M. Witmer. 2010. Cartilaginous Epiphyses in Extant Archosaurs and Their Implications for Reconstructing Limb Function in Dinosaurs. PLoS ONE 5:e13120.

Malda, J., J. C. de Grauw, K. E. M. Benders, M. J. L. Kik, C. H. A. van de Lest, L. B. Creemers, W. J. A. Dhert, and P. R. van Weeren. 2013. Of Mice, Men and Elephants: The Relation between Articular Cartilage Thickness and Body Mass. PLoS ONE 8:e57683.

McGowan, C. 1999. A Practical Guide to Vertebrate Mechanics. Cambridge University Press, New York, 316 pp.

Prothero, D. R. 2013. Rhinoceros Giants: The Paleobiology of Indricotheres. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 160 pp.

Prothero, D., and R. Schoch. 2002. Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 315 pp.

Simon, W. H., S. Friedenberg, and S. Richardson. 1973. Joint congruence: a correlation of joint congruence and thickness of articular cartilage in dogs. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American) 55:1614–1620.

Tsai, H., and C. M. Holliday. 2012. Anatomy of archosaur pelvic soft tissues and its significance for interpreting hindlimb function. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Program and Abstracts:184.

Vogel, S. 2003. Comparative Biomechanics: Life’s Physical World. Princeton University Press, 580 pp.

Yates, A. M., M. F. Bonnan, and J. Neveling. 2011. A new basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31:610–625.

Due to requests for a sampler of my forthcoming book from Indiana University Press, The Bare Bones, I am now making available a PDF of the first chapter. I think this will give you a feel for the tone of the book.

Due to requests for a sampler of my forthcoming book from Indiana University Press, The Bare Bones, I am now making available a PDF of the first chapter. I think this will give you a feel for the tone of the book.