I am happy to report on a new sauropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa! The dinosaur, Pulanesaura, was discovered in 2004 and has been a long time coming to press. Now, she’s finally here.

When I was maybe four or five years old, I remember reading a dinosaur book with my mother. The book described for children how dinosaurs were discovered and excavated in the field, and then how the bones were reassembled back in the lab. What I don’t remember, but I have been told, was that at some point during the explanation of how dinosaurs were unearthed, I interjected, “And then they have lunch.”

I was five years old in 1978. Fast-forward to the fall of 2004, and my 31-year-old self is standing in the rain at Spion Kop farm in the Free State of South Africa marveling at the large limb bones poking out of a section of the upper Elliot Formation. I don’t recall having lunch at that moment, but I do remember being excited, and being grateful that I was part of a team, headed by Adam Yates, charged with exploring these Early Jurassic rocks. National Geographic had sponsored our grant to pursue promising bones issuing forth from these rocks, and although we did not immediately know we had a new dinosaur, there was a good possibility we did.

Myself above two tibia bones (tibiae) from what would become known as Pulanesaura in 2004 … it was a less rainy day that day.

Why South Africa? As it turns out, South Africa has many exposures of Lower Jurassic rocks that record a very significant time in dinosaur evolution. The earliest true dinosaurs appeared in the Triassic period about 235 million years ago (Ma) but remained relatively small to medium-sized animals that were in competition with other vertebrate groups vying for dominance in a harsh world. During the Triassic period, all the continents were amalgamated into a single supercontinent dubbed Pangea. Although to a modern traveler the thought of Pangea sounds amazing (imagine riding a train from North America over to Europe or driving from South America into Antarctica, Africa, or Australia), ecologically this was disastrous. A huge expanse of Pangea was landlocked and nearly devoid of water, making it both hot and uninhabitable. Moreover, sea levels were also drastically lower, creating fewer areas for marine life to thrive. Thus, Pangea took a huge toll on the animals that preceded the dinosaurs. In fact, the largest mass extinction in the past 540 million years occurred just prior to the Triassic period, wiping out a majority of life on the planet.

During the Early Jurassic (starting about 200 Ma), Pangea began to unzip and break up into separate landmasses, and part of the effect of this was to bring water into regions it hadn’t been in millions of years, supporting more plants and, in turn, the animals that fed on them. It is also at this critical juncture that the sauropodomorph dinosaurs began to become larger-bodied and more diverse so that by the end of the Jurassic period (about 145 Ma), many of these herbivores were tipping the scales at 20-30 metric tons! Sauropodomorphs started out as small to medium-sized bipedal herbivores that used their long necks and grasping hands to consume foliage at different heights in their environment. Sauropods became fully quadrupedal giants with elongate necks that acted as efficient food-gathering feeding booms, sweeping across swaths of vegetation while the herbivore stayed put. And this transition from mostly bipedal herbivores eating with their hands and necks to giant quadrupeds that relied solely on long necks to feed occurred right around the Early Jurassic period about 200 Ma. So, if you want to understand the beginnings of this trend towards gigantism in the sauropodomorph dinosaurs, you need to search for fossils in Early Jurassic rocks … and that brings us back to me standing in the rain at Spion Kop on the upper Elliot Formation staring at the large bones coming out of the ground.

Those bones we were unearthing would end up being a sauropod new to science named Pulanesaura that my colleagues and I have published on this week in Nature Scientific Reports. The lead author, Blair McPhee, is a Ph.D. student at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa who took on this dinosaur for his dissertation. Remember that we discovered Pulanesaura in 2004? Why didn’t we publish on this animal earlier? For a number of reasons collectively called life. Between 2009 and 2011, we did publish on two other sauropodomorph dinosaurs from Spion Kop, so that took up some time. But more significantly, Adam Yates and I had major life-changing moves to new employers: Adam to the Museum of Central Australia in Alice Springs; me to Stockton University. And so poor Pulanesaura was languishing. Therefore, when Blair approached us about describing Pulanesaura for his Ph.D., we were enthusiastically supportive. I was especially pleased to see Blair at the helm of the description. I am beyond happy that a South African Ph.D. student is the lead author on the description of a native South African dinosaur. His persistence and perseverance on this project is why the world now knows about Pulanesaura.

Why Pulanesaura? Well, the name means “rain bringer” in Sesotho, which is fitting since we always seemed to get rained on during the excavation of this dinosaur. And the publication of “Rain Bringer” has finally brought home a trilogy of sauropodomorph dinosaurs and the complex story they tell of what was happening in the Early Jurassic at what is now the Spion Kop farm.

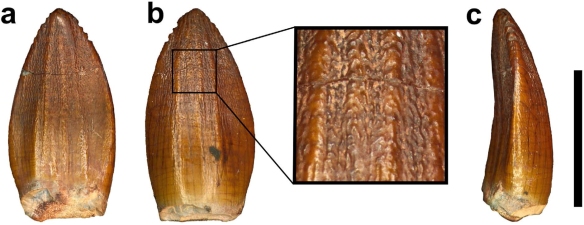

First things first – how do we know Pulanesaura is a sauropod? A number of clues point the way. For one thing, although we did not find a skull, we found teeth. The teeth of sauropods, unlike their sauropodomorph brethren, have a spoon- or spatula-like profile and have wrinkled enamel. The teeth of Pulanesaura certainly fit the bill there.

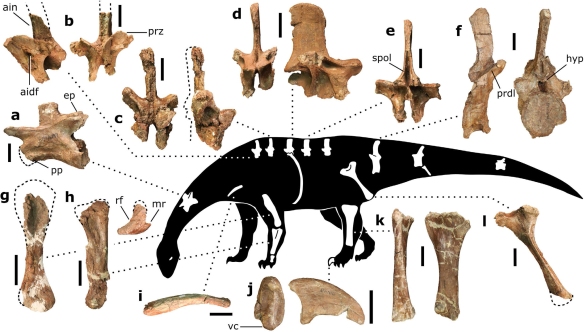

Next, being large, sauropods braced their vertebral column with extra joints in their backbones (vertebrae) – a portion of this extra joint is called the hyposphene. The body vertebrae we have of Pulanesaura only preserve their tops (the hyposphene is located on the bottom-half of the vertebra) but luckily a full tail (caudal) vertebra is preserved, and that has a hyposphene. We are also fortunate that part of the forelimb was preserved. The ulna bone in sauropods cradles the other forearm bone, the radius, by wrapping around it from behind. In sauropods, a wide, triangular depression is present on the ulna where the radius sits. Although the ulna of Pulanesaura is a bit crushed and scrappy, it was intact enough to show that, yes, indeed, such a depression for the radius was there. These features and more showed us that this dinosaur was certainly a true sauropod.

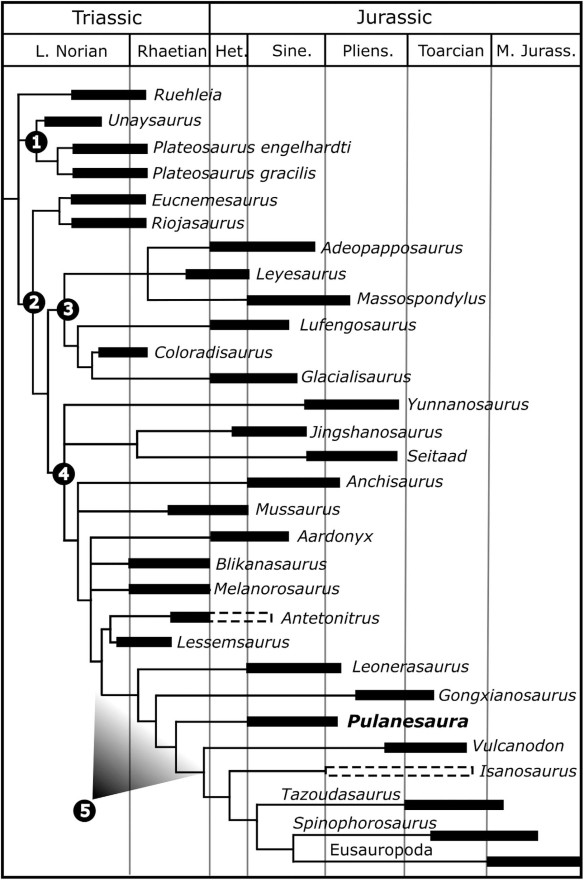

How do we know Pulanesaura is new to science? Using a method called cladistics, the suite of features for Pulanesaura was compared to other sauropodomorphs and sauropods from South Africa and around the globe. Its unique combination of features show that it is not a member of previously known sauropodomorph or sauropod dinosaurs, but falls along its own branch of the dinosaur family tree near the common ancestor of all sauropod dinosaurs. At the moment, it is very difficult to tell the difference between a true early sauropod and a sauropodomorph very close to the common ancestor of sauropods. Given the data we have for Pulanesaura, we find it most likely to be a very early sauropod. Certainly, future studies and perhaps more material of Pulanesaura will clarify this picture.

How big was Pulanesaura? We certainly don’t have a complete skeleton of this herbivore, but we have enough bones from enough areas of the body to infer that this animal stretched nearly 8 meters (about 26 feet) long and stood about 2 meters (about 6.5 feet) high at the hip. That may seem big, but it’s small for a sauropod.

Why is Pulanesaura significant? The traditional picture of sauropodomorph evolution is that when true sauropods came onto the scene, the other sauropodomorphs were pushed aside, their small body size and “inferior” anatomy undone by the larger herbivores. But Pulanesaurua turns this notion on its head because, living alongside it at Spion Kop were other sauropodomorph dinosaurs with very different anatomies. Adam, Johann, myself, and others have described two of these other sauropodomorphs, both also from Spion Kop. One, Aardonyx, was a 7 meter long sauropodomorph capable of assuming both a bipedal and quadrupedal posture; and another, Arcusaurus, was a small, juvenile sauropodomorph with a hold-over of more primitive features. And one of the things these other sauropodomorphs had going for them was that they could feed at different heights and use their forelimbs to direct foliage to the mouth. In contrast, the anatomy of Pulanesaura shows that it was an obligate quadruped (it could not stand bipedally on its hind legs), which would have restricted its vertical reach for vegetation compared with these other sauropodomorphs. However, the single neck (cervical) vertebra we have for Pulanesaura has joints that were spaced and angled (much like those of other sauropods) such that they would have allowed for a larger range of neck motion than in other contemporaneous sauropodomorphs. In other words, although Pulanesaura could not rear up and extend its neck into the trees, it could stand still and more efficiently crop foliage over a wider range. We suggest Pulanesaura shows us the incipient stages of what sauropods became very good at: they stood in one place and swept their tiny heads across a sea of vegetation. As the Jurassic period wore on, and vegetation became larger and more widespread, the advantages conferred by a body which conserved energy by standing still and sweeping a long neck across swaths of plants would ultimately select for sauropods and not their bipedal cousins.

It would have been difficult to explain to my five-year-old self that it would be many lunch breaks from the initial discoveries at Spion Kop to their final reveal to the public. But it has been worth the wait. I consider myself to be very fortunate to have the privilege of working with so many enthusiastic and talented people. Moreover, it is important to stress that cooperation with the farmers at Spion Kop was invaluable. Partnerships with farmers are a great benefit to paleontology in South Africa. Farmers know their land well, and they’re always spotting interesting things. It’s such a pleasure to work with people who value their heritage and to help them learn more about it. Because of such mutual respect and interest in South Africa’s prehistory, we now have a much richer picture and appreciation of a pivotal moment in sauropod dinosaur history that would not otherwise be possible.

And my inner five-year-old most certainly approves!

Excellent write up and you strike a nice balance between making it understandable & approachable but still technical. Can I ask what led you to surmise that this animal could not rear up on its hind legs as is often suggested for latter sauropods? Having a bipedal evolutionary legacy should allow some degree of potential for bipedal rearing.

Hi Duane,

Thanks, and excellent question. In most bipedal dinosaurs, the humerus (upper arm bone) has a depression (fossa) on the distal, cranial-facing (front-facing) portion that provides room for the elbow to flex. In Pulanesaura and other sauropods, this fossa is absent, which would preclude the kind of elbow flexion necessary to make the arms “useful” as grasping appendages. Certainly, we cannot absolutely rule out that Pulanesaura and other sauropods never reared up, but it was likely less frequent and less efficient than remaining on all-fours.

What happened to the age of Isanosaurus?

Never mind, that’s explained in ref. 17 of the paper!

Hi David,

Yes, you caught it. =) Cheers, Matt

What’s with the scare-quotes around “Kotasaurus” in the paper? Is it still considered valid?

I’m glad to see somebody acknowledging the sad situation that is the phylogenetic definition of Sauropoda. Damn transitional forms, making neat categorization difficult.

Hi John,

I’m no taxonomist (that is why we work in teams, right?) but my understanding of the situation from Adam and Blair is that Kotasaurus may be problematic and may not be valid, hence the, as you say, scare-quotes. Adam Yates addresses this in his 2007 paper on the skull of Melanorosaurus. My hypothesis about sauropod relationships (based on the data and conversations with Adam) is that they definitely nestle within what we used to call “prosauropods” and that there is this sort of gradual transition. Sauropod evolution, especially early on, seems to be the epitome of mosaic evolution. For example, I had hypothesized that a U-shaped manus and the interlocking radius and ulna in sauropods would have appeared temporally, but that is just not the case. The forearm features appear before the hand changes shape, for example. In any case, I love these dinosaurs – they are so weird you kind of have to admire that they did so well.

Matt

more of a general question; my 3 year old son loves dinosaurs- he knows the names, the eating habits, their method of locomotion and some major characteristics of about 25 -30 different animals, is there something you can recommend that isn’t technical but will continue to stoke his love of learning about dinosaurs?

Hi Robert,

I don’t know if you have this book, but the National Geographic Little Kids First Big Book of Dinosaurs would be a great choice: http://www.amazon.com/National-Geographic-Little-First-Dinosaurs/dp/1426308469/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1440091303&sr=8-2&keywords=dinosaurs. The books in that series are pitched perfect for kids, and the dinosaur book has parent tips at the back.

Cheers,

Dr. Matt

Pingback: Paleo Profile: Pulanesaura eocollum – Phenomena: Laelaps