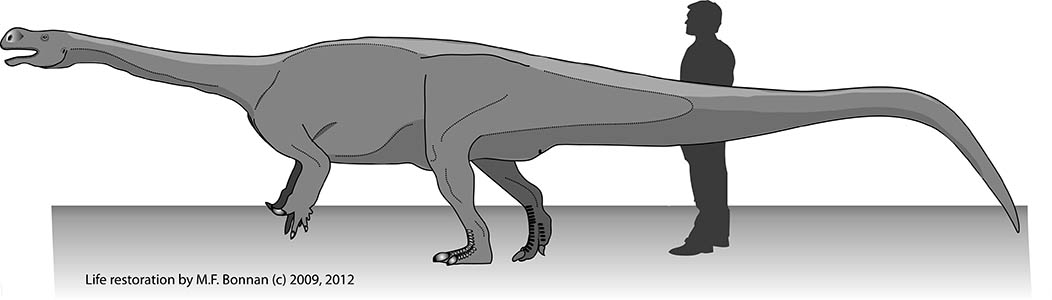

In the last two posts, I outlined many of the reasons why birds and dinosaurs have been “estranged” and are now being reunited as members of the same clade: Dinosauria. If you haven’t read these first two posts, check them out:

So, at this point if you’re still not convinced that birds are indeed the living dinosaurs among us, here is one more thing to consider. Let me take you by the hand …

So this: the earliest predatory dinosaurs had five digits, but the main three digits were I, II, and III, not II, III, and IV. In fact, during predatory dinosaur evolution, digits IV and V decrease in size until all that is left are I, II, and III. This contradiction between the digit identities of bird hands and predatory dinosaur hands has been held up as the ultimate “proof” that all the amazing similarities between birds and dinosaurs are just that: amazing convergence.

Enter the past two decades of embryonic science, studies of evo-devo (evolutionary development), and a proliferation of studies combining old-school developmental anatomy with new-school gene studies. It turns out that the digit identities in the hand are not set like permanent blueprints, but develop from the expression of various developmental genes to concentrations of various proteins. Without going into great detail, we now know that the identity that digits assume (that is, whether they become I or V or something else) depends on how much of a concentration of particular proteins these regions of the hand were exposed to during development. Simply put, higher concentrations of certain proteins trigger genes that, when transcribed and translated (i.e., expressed), ultimately create proteins that form digit I, II, III, IV, or V.

Intriguingly, this means that the relative position of a digit in the embryo’s hand and what that digit actually becomes are different. In other words, a digit in position II could become a digit I if the concentration of various proteins and the expression of certain genes are changed. This has been called the Frame-shift Hypothesis. In this case, the “frame” is the region of gene expression that gives digits their identities, whereas the how this gradient moves in the developing hand is the “shift.” What this all means is that just because you develop a digit in your hand where digit II should be doesn’t at all guarantee that it will become digit II. It might become digit I, for example, depending on the frameshift.

What this all means is that, hypothetically, at some point during predatory dinosaur evolution, the anlagens that were in positions II, III, and IV frame-shfited to I, II, and III. This frameshift would, of course, “solve” the digital confusion between birds and dinosaurs, but of course this hypothesis has been questioned and there was no fossil evidence of it occurring in dinosaurs … until recently.

A new Jurassic ceratosaur (a primitive type of predatory dinosaur) from China called Limusaurus preserved a complete hand that looks like an embryonic bird hand! See for yourself: Figure 2 in their paper. Now, compare that figure of the ceratosaur hand back to the ostrich hand. I find this absolutely fascinating and was floored to see a dinosaur hand that looked like something undergoing the hypothesized frameshift. Here, captured in stone for millions of years, is what you would predict to see in a transitional form going from the primitive predatory dinosaur digit arrangement to the birdy one. Note in the Limusaurus hand figure that where the first digit is is a splint, like in a bird embryo, and next to that, the digit in the typical place of digit II, is something that looks an awful lot like digit I.

So, to conclude my thread, let me say that it is not at all parsimonious at this point in time to separate birds from dinosaurs. That is equivalent to separating you from mammals. It is no longer enough to argue that all the similarities between dinosaurs and birds are due strictly to an amazing amount of convergent evolution. We have unique skeletal features only birds and dinosaurs share, we have dinosaurs that could not possibly fly possessing feathers, and we even have fossil support to explain why bird and dinosaur hands match up after all.

And finally back to the recent paper that inspired this thread in the first place: Birds have paedomorphic dinosaur skulls. Paedomorphosis is the retention of juvenilized features into adulthood. In other words, the proportions of the larva, infant, or juvenile remain relatively unaltered as adults. This occurs a lot more often in nature than you may realize. Essentially, the scientists Bhullar and colleagues used a shape analysis technique I have used myself: geometric morphometrics. This technique analyzes changes in bony landmarks across numerous specimens and provides a mathematical test to see whether the changes predicted are actually significant. What Bhullar and colleagues discovered was that bird skulls grow as if they were juvenilized dinosaur skulls! Yet another nail in the coffin (scientifically) for the vague claim that birds cannot be dinosaurs.

Let’s face it: birds are dinosaurs. I emphasize that I say this in the scientific sense of “certainty.” Although we can’t be 100% certain in science, these data show overwhelmingly that birds are part of the dinosaur family tree. When you realize that there are over 10,000 species of living birds but only 4600 or so species of living mammals, you realize it is still the Age of Dinosaurs after all.